By Linda Diamond, founder and former president of Consortium on Reaching Excellence in Education

Published by Collaborative Classroom

“When we think about learning, we typically focus on getting information into students’ heads. What if, instead, we focus on getting information out of students’ heads?”

~ Pooja K. Agarwal, Powerful Teaching: Unleash the Science of Learning

A team of educators is deep in a review of instructional materials, seeking a program that aligns with the research on effective reading instruction. These educators are well versed in structured literacy, and they are vetting instructional materials for key components such as phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension, background knowledge, writing, and oral language.

This diligent team is on track to successfully select effective materials, with one exception. What are they missing?

The answer: an attention to instructional design and the science of learning. As they vet materials, these reviewers should also be asking: “Does this program present and teach information in ways that maximize students’ learning?”

Looking for Sufficient, Deliberate Practice

In this blog we’ll unpack a simple, actionable way to attend to the science of learning and instructional design when reviewing materials, namely the presence (or absence) of sufficient practice.

Practice is a critical ingredient in maximizing our ability to learn and retain new information. The science of learning tells us several important things about practice, including:

- There are different types of practice.

- Both the amount and the frequency of these different types of practice are important factors in successful learning and retention.

Unfortunately, the presence of practice is not a given. Many commercial instructional materials lack sufficient practice. Even when the instruction includes practice, the types of practice, their amounts, and their frequency are not optimal for students’ learning and retention.

“Practice is a critical ingredient in maximizing our ability to learn and retain new information.”

Too often, schools purchase and faithfully implement a new highly rated curriculum only to discover that many children are not learning and retaining what has been taught.”

A lack of sufficient, deliberate practice may be the cause.

What Does the Science of Learning Tell Us About Initial Learning, Practice, and Retention?

Cognitive Load, Memory, and Initial Learning

During initial learning, our working memory can hold only a limited amount of new information before bottlenecks occur.

When educators present students with too much new or challenging information, we increase the potential for cognitive overload of working memory. By presenting information clearly, organized carefully, and broken down into manageable chunks, we help students process the content.

After that initial learning, practice plays an equally important role. It functions as a bridge, helping students transfer their new learning to long-term memory, thereby freeing up their working memory.

Deliberate and Purposeful Practice

Students need lots of practice to build retention and further consolidate new learning into long-term memory—but not just any practice.

Hughes and Riccomini describe the essential practice as deliberate and purposeful: “practice that goes beyond rote repetition and involves practicing for a purpose (e.g., fluent retrieval and generalization) with the deliberate goal of long-term improvement of skill performance” (2019, p. 406).

They further describe instructional considerations that are necessary to make practice most effective:

- Assigning further independent practice after students have demonstrated a high rate of initial mastery with careful teacher monitoring

- Modeling how to complete practice activities

- Combining practice activities, for example, spaced practice with retrieval practice

- Using appropriate and affirming corrective feedback (Hattie and Yates, 2014)

Vaughn and Fletcher (2023) also emphasize that deliberate practice is goal-oriented, for example improving automaticity with decoding words or enhancing fluency. They describe four important components of deliberate practice that echo the findings of Hughes and Riccomini (p.19):

- Having well-defined goals

- Building interest in achieving the goals

- Providing feedback

- Building in opportunities for additional practice

Research by Doabler and colleagues (2018) also noted that components 3 and 4, feedback and amount of practice opportunities, are the most powerful components of explicit instruction.

Furthermore, they found, especially for students with disabilities, that there should be “three times more independent practice opportunities than instruction (i.e., modeling, describing) when teaching new academic skills” (cited in Hughes and Riccomini [2019, p. 406]).

“Students need lots of practice to build retention and further consolidate new learning into long-term memory—but not just any practice.”

Given the importance of deliberate practice, let’s look at the different types of practice that should be included in instructional materials. These types of practice are consistent with both the science of reading and with what cognitive science tells us about how learning happens.

As we’ll see, practice is where the science of reading and the science of learning merge.

Sufficient, Deliberate Practice: Three Types of Practice to Look For

How do we move new learning into long-term learning for retention? We practice—but not just blocked or massed practice.

Beyond initial, explicit instruction and guided practice, we must consider three important types of deliberate practice:

- Spaced or distributed practice

- Cumulative and interleaved practice

- Retrieval practice

“Students need all three types of practice to build the circuitry for long-term memory, to transfer newly learned knowledge to long-term knowledge, and to reduce forgetting.”

Students need all three types of practice to build the circuitry for long-term memory, to transfer newly learned knowledge to long-term knowledge, and to reduce forgetting. These types of deliberate practice should be transparently obvious in any purchased curriculum.

Now let’s explore each type of practice.

Type One: Distributed or Spaced Practice

Distributed or spaced practice helps cement the learning of the new content which lays the prerequisites for the next content. Distributed/spaced practice involves scheduling relatively short practice sessions over time using predetermined time intervals (e.g., every 3 days).

Spaced practice builds retention and consolidation in long-term memory (Hughes and Riccomini, 2019). In their article for teaching vocabulary to multilingual learners, Amanda Edmonds, Emilie Gerbier, Katerina Palasis and Shona Whyte (2021) found that widely spaced and more challenging repeated practice is essential to vocabulary learning.

“Distributed or spaced practice helps cement the learning of the new content which lays the prerequisites for the next content.”

Unfortunately, too often educators may feel that using instructional time for repetition of previously taught skills and knowledge rather than to new materials is wasteful.

Yet research on distributed practice and language learning emphasizes the importance of “repeated, gradually enhanced exposures to the same material” (Edmonds et al., 2021, p.15). They point out that each encounter with a new word strengthens retention and deepens the understanding of that word.

Distributed or spaced practice, however, must go beyond massed or blocked practice of the same newly taught skills. Brown, Roediger, and McDaniel (2014) found that by spacing practice we can significantly increase the amount of learning that students remember; whereas, learning from massed practice alone is often forgotten.

Type Two: Cumulative and Interleaved Practice

To make distributed practice even more effective we should combine it with cumulative and interleaved practice:

- Cumulative practice requires that newly taught but related skills are added to previously taught skills as they are acquired. This provides distributed practice for multiple skills within one session.

- Interleaved practice involves mixing the order of skills and problems to be practiced by distributing them in a random (e.g. ABACBABCA) rather than a massed or blocked fashion e.g. AAABBBCCC).

- Cumulative and interleaved practice, also referred to as “variability of practice” (Kirschner & Hendrick, 2024, p. 76) causes the learner to discriminate, which in turn leads to increased transfer of learning.

Type Three: Retrieval Practice

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, retrieval practice is essential for long term memory. Retrieval practice requires retrieving specific skills and knowledge from memory without scaffolds, cues, or teacher prompts (Hughes & Riccomini, 2019).

“Retrieval practice requires retrieving specific skills and knowledge from memory without scaffolds, cues, or teacher prompts.”

According to Agarwal, Roediger, McDaniel, & McDermott (2020), “Retrieval practice is a strategy in which calling information to mind subsequently enhances and boosts learning” (p. 2). Retrieval practice makes learning last more effectively than reteaching the original material.

Can a Curriculum Incorporate These Types of Practice?

What do these types of practice look like in an actual curriculum?

An answer can be found in the K–12 accelerative foundational skills program SIPPS, which was designed in alignment with the science of learning.

Throughout the SIPPS curriculum, the different types of research-based practice are clearly evident. Sufficient and deliberate practice — including distributed, cumulative and retrieval practice — are regular features of the lessons.

In this section of the blog, let’s examine examples of these types of practice in SIPPS lessons.

Lesson Examples of Practice

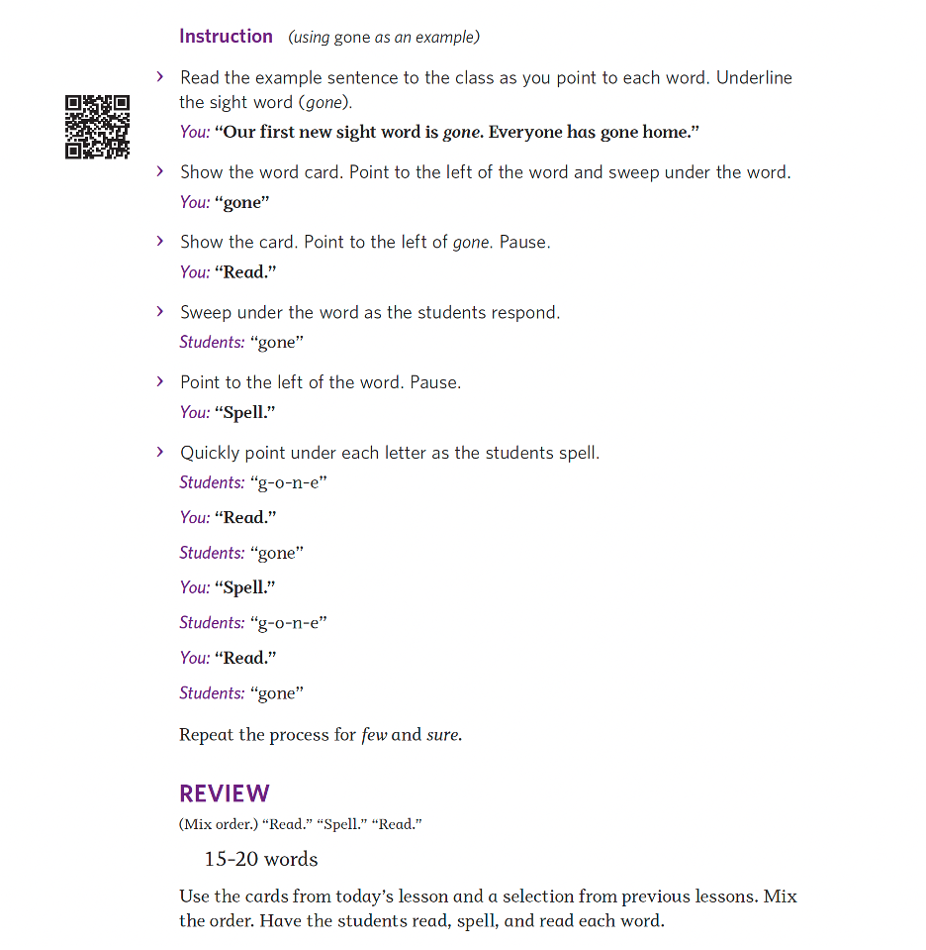

Figure 1 is an example of initial instruction followed by a mixed, cumulative review, with retrieval practice of previously learned words.

In this figure, the students review not only the new word they have learned but also follow with a cumulative review of words from previous lessons.

Because students do this review with no direct support from the teacher, it is also an example of retrieval practice from memory.

Figure 1:

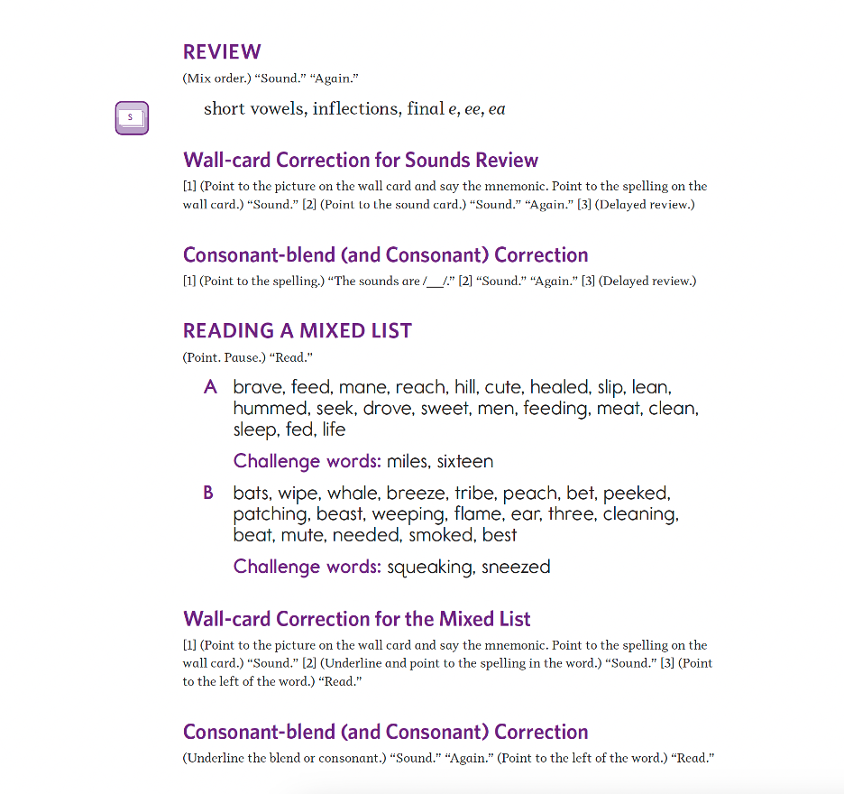

Figure 2 represents a cumulative SIPPS lesson with corrective feedback, requiring discrimination and retrieval.

The mixed list portion of the lesson is an example of retrieval practice. The teacher does not say the sounds but simply points at them, and the students must read the words on their own, retrieving the sound-spellings from memory.

This part of the lesson is also an example of cumulative and interleaved practice. Students must discriminate between the different long-vowel words, some with silent ‘e’, some with ‘ea’, and some with ‘ee.’

In addition, the review includes short vowel words, so that students must retrieve from memory their prior learning of the different short vowel sound-spellings within the list.

Figure 2:

The mixed list portion of the lesson is an example of retrieval practice. The teacher does not say the sounds but simply points at them, and the students must read the words on their own, retrieving the sound-spellings from memory.

This part of the lesson is also an example of cumulative and interleaved practice. Students must discriminate between the different long-vowel words, some with silent ‘e’, some with ‘ea’, and some with ‘ee.’

In addition, the review includes short vowel words, so that students must retrieve from memory their prior learning of the different short vowel sound-spellings within the list.

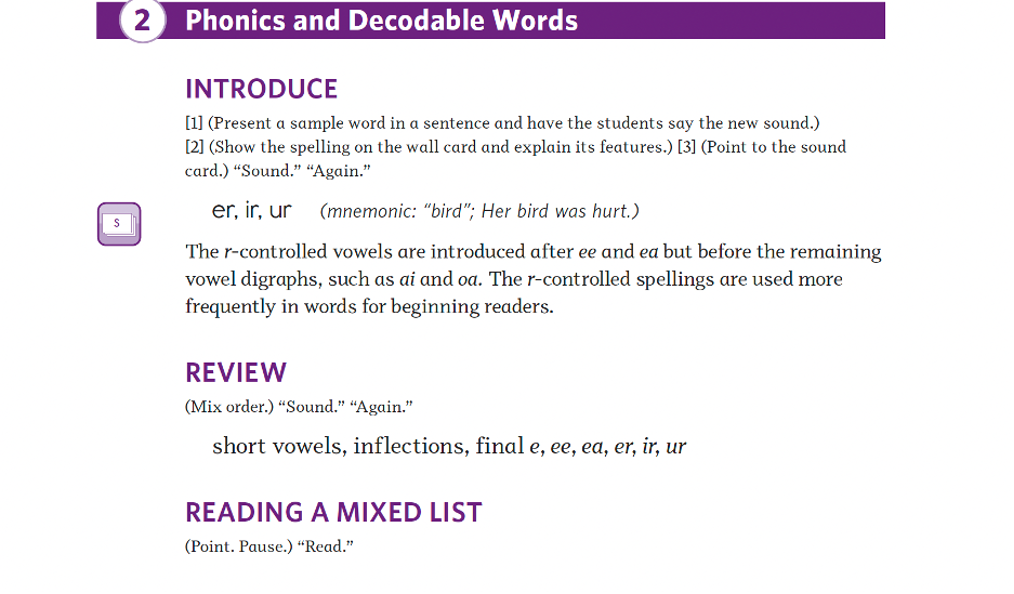

Figure 3 shows an excerpt from a SIPPS lesson that includes cumulative, distributed practice of a mixed list that provides retrieval practice from memory, with the teacher simply pointing and saying, “sound.”

Here again, the review portion includes a mixed review of the r-controlled sound-spellings and long -e spellings.

Figure 3:

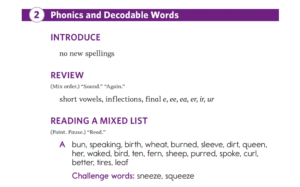

Figure 4 shows a cumulative, distributed, retrieval activity requiring a great deal of discrimination.

In this figure students read a mixed, cumulative list without teacher scaffolding.

Students must discriminate and retrieve from memory how to read various short vowel words, different long -e sound-spelling words (and even multisyllabic words with inflectional endings). Because the list is designed randomly, it is a good example of interleaving practice.

Figure 4:

Conclusion: Attending to Sufficient, Deliberate Practice

To be able to identify practice within instructional materials is important, but to actually find sufficient practice that aligns to the cognitive science is rare.

When vetting instructional materials, we must find more than the components of effective, evidence-based reading instruction. Look closely at the design of the instruction in those components. We know programs are most effective when they intentionally build in sufficient, deliberate practice based on the principles of learning.

We have abundant evidence of the effectiveness of Direct Instruction programs (Stockard, et al., 2018), and we have equally strong evidence from schools using a similar direct instruction design, with SIPPS being one example.

“We know programs are most effective when they intentionally build in sufficient, deliberate practice based on the principles of learning.”

When considering instructional materials to purchase, educators would do well to examine lessons for sufficiency of amount, frequency, and types of practice.

Only then will we have the materials and the instruction we need to ensure that our students learn and retain what we have taught.

References

Agarwal, P. K., & Bain, P. M. (2019). Powerful teaching: unleash the science of learning. Jossey-Bass.

Agarwal, P., Roediger, H., Mcdaniel, M., & Mcdermott, K. (2020). How to use retrieval practice to improve learning retrieval guide. http://pdf.retrievalpractice.org/RetrievalPracticeGuide.pdf

Brown, P. C., Roediger III, H. L., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Harvard University Press.

Doabler, C. T., Stoolmiller, M., Kennedy, P. C., Nelson, N. J., Clarke, B., Gearin, B., Fien, H., Smolkowski, K., & Baker, S. K. (2018). Do Components of Explicit Instruction Explain the Differential Effectiveness of a Core Mathematics Program for Kindergarten Students With Mathematics Difficulties? A Mediated Moderation Analysis. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 44(3), 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534508418758364

Edmonds, A., Gerbier, E., Palasis, K., & Whyte, S. (2021). Understanding the distributed practice effect and its relevance for the teaching and learning of L2 vocabulary. Lexis, 18. https://doi.org/10.4000/lexis.5652

Hattie, J., & Yates, G. C. R. (2014). Visible learning and the science of how we learn. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Hughes, C. A., & Riccomini, P. J. (2019). Purposeful Independent Practice Procedures: An Introduction to the Special Issue. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 51(6), 405–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/0040059919850067

Kirschner, P., & Hendrick, C. (2024). How Learning Happens Seminal Works in Educational Psychology and what they mean in practice (second). Routledge. (Original work published 2020)

Parkway, C. for the C. C. 1001 M. V., & Alameda, S. 110. (n.d.). The Evidence Base for SIPPS. Collaborative Classroom. https://www.collaborativeclassroom.org/evidence-base/research-sipps/

Stockard, J., Wood, T. W., Coughlin, C., & Rasplica Khoury, C. (2018). The Effectiveness of Direct Instruction Curricula: A Meta-Analysis of a Half Century of Research. Review of Educational Research, 88(4), 479–507. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317751919

Transform Teaching with the Science of Learning. (2019). A Powerful Strategy to Improve Learning. A Powerful Strategy to Improve Learning. https://www.retrievalpractice.org/

Vaughn, S., & Fletcher, J. (2023). The Practice Gap. Perspectives on Language and Literacy, 49(1), 15–19.